Claire's Original Art Greeting Cards

There is nothing that says I care like a real snail-mail greeting card!

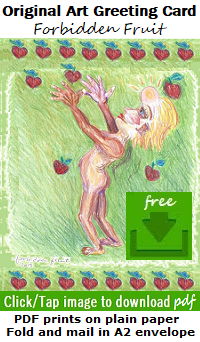

Click on a picture above for a plain-paper printable greeting card pdf.

Print on regular 8.5 by 11 printer paper. Fold twice so that the art is on the front and the title and copyright are on the back.

Write your greeting on the inside.

Mail in an A2 Invitation Envelope.

Claire's Original Art Greeting Cards

There is nothing that says I care like a real snail-mail greeting card!

Click on a picture above for a plain-paper printable greeting card pdf.

Print on regular 8.5 by 11 printer paper. Fold twice so that the art is on the front and the title and copyright are on the back.

Write your greeting on the inside.

Mail in an A2 Invitation Envelope.Greenspan Builds His Brand

March 26th, 2021 · No Comments

Free Donuts—Take All You Want! We’re throwing away the scales, and food is free! We trust you to eat responsibly.

Our pals in Washington deregulated banking, then they dropped interest rates to near zero. It was a free-for-all! “There never would have been a sub-prime mortgage crisis if the Fed had been alert. Monetary policy was too accommodative. Rates of 1 percent were bound to encourage all kinds of risky behavior.” (Sebastian Mallaby quoting Anna Schwartz; The Man Who Knew: The Life and Times of Alan Greenspan page 655 hardcopy)

Mr. Greenspan knew that markets are given to bubbles. Years earlier, Mr. Greenspan had tried to talk down the market, hoping asset managers would listen, but his “irrational exuberance” speech had little effect, and he gave up on the professorial lecture as tool to modify market behavior.

This time, for the 2008 meltdown, Greenspan gave a whiny excuse for doing nothing: Bubbles are too hard to anticipate, we’d have to cut off short-term credit and “break the back of the economy.” (Mallaby quoting Greenspan page 655) Uh, really? Like that didn’t happen anyway? Greenspan assumed Fed could clean up such a disaster with easy money, or perhaps that in combination with strong-arming major players into helping with bailouts, like they did for Long Term Capital Management in 1998. Greenspan took on the easy money part and left the dirty work to others.

He dodged managing asset prices and instead focused on inflation, despite the findings, according to his own staff’s studies, that inflation was not, in and of itself, harmful. Greenspan’s target of 2% was, basically, pulled out of the air.

Regulations are another tool in the central banker kit, but regulations, of course, can be problematic. Money flows toward the best returns, so any regulation might encourage off shore activity. Regulation Q, limiting interest rates, “hamstrung” the S&Ls (page 129) and encouraged “dollar savings to flee to Europe” (page 534).

When community banking and investment banking were regulated to be separate, the largest U.S. bank was a mere 26th in the world. Now, according to Wikipedia, our largest is number 7. Is that good? bad? important? Is having large financial institutions incorporated on our shores a reason to deregulate?

Mr. Greenspan, long a laissez faire Ayn Randian*, said regulation was just too difficult, that the financiers have a better understanding of risk than do the regulators and that Wall Street would find ways to get around whatever rules our civil servants designed. He didn’t anticipate that Wall Street’s quants would dream up products their CFOs did not understand. His idea was that derivatives would distribute risk where it was best managed, but he closed his eyes to their complexity, never mind that he’d witnessed Merrill Lynch bamboozle Orange County.

Neither Democrats nor Republicans wanted to regulate. Effective regulation would require a significant overhaul. Disparate agencies vie for power and financial entities can configure themselves to be regulated by the regulator of their choice. Yes, it’s difficult, but does that mean you shouldn’t try? Greenspan showed no interest in a difficult fight, and instead focused on inflation, where he thought he might have success. Managing inflation was easier, especially when it cooperated so well that he could keep rates low and please the administration–whether Democrat or Republican, the administration wants to goose the economy with easy money. That his low interest rates would drive an overwhelming appetite for better returns and therefore sabotage risk aversion, seems to have escaped him.

Mallaby explains that Greenspan was quite the politician and writes that he “was a master of evasion” (page 427). For example, when he wanted to disabuse politicians of their faith in supply side economics, he sent surrogates to deliver the message in order that he might stay in the good graces of those with the power to make appointments. Before a congressional committee, he could talk in circles such that our representatives would be left thinking that if they’d just listened more carefully they would understand, when really, Mr. Greenspan was just baffling with bullshit.

Greenspan was more interested in building his brand than he was in actually working, because in actually working he might fail and, in that failure, lose his reputation as The Man Who Knew. Having read Mallaby’s account, I’d say that happen anyway.

* I’ve never understood Greenspan’s fascination with Ayn Rand. She wrote fiction!

Tags: Books · Economics and Finance · Politics

0 responses so far ↓

There are no comments yet...Kick things off by filling out the form below.

Leave a Comment